Safflower (Carthamus tinctorius) is a thistle-like plant that was widely grown from the Mediterranean across to China, as its flowers yield an attractive red dye*. It is still cropped in modern times, but for cooking oil. The flowers are also very rich in yellow pigment – amusingly this is a contaminant which has to be rinsed away before the more desirable red dye can be extracted.

Ingredients

This describes a ‘mini-bath’ I used for dyeing small strips of veg-tanned sheepskin to use as decorative trim on pair of shoes. I wanted the dye to be strong and effective, so volume was kept to a minimum – just enough liquid to cover items and let them move around a bit. I think the bath could even be reused a few times (results may not match from dip to dip though). It should work on most traditionally preserved leathers. Glass jars are good for mordanting and dye baths.

Mordant (2% alum): Alum 10 g; cream of tartar 4 g. Dissolve in 500 ml of warm water. Note – I don’t know how much the cream of tartar (a.k.a. salts of wine; potassium bitartrate) helps, if at all.

Safflower yellow dye bath: Prepare just before you are ready to dye. Cover 15 g of safflower petals with 375 ml (1-1/2 cups) water at room temperature. Stand for 1 hour, mixing occasionally. Strain though a cloth into another receptacle, squeezing out remaining liquid. Return the petals to the original jar, add 125 ml (1/2 cup) more water, mix and stand for another hour, strain and combine with first extract. Note – as mentioned, these petals can be processed further for red dyeing – see sources below for methods.

Procedure

1. Soak your leather pieces in the cooled mordant solution for 3 hours, or even overnight – long soaks or even refreshing the solution can help to lighten up the shade of your leather by removing some tannins. Move them around occasionally. Remove leather before you are ready to begin dyeing. Lay it out flat in a shady draft-free spot for 30 min.

2. Add the leather to the dyebath. No heat is required. Move it around, turn it over for the first few minutes, and every 20 minutes or so thereafter. Push under any part that isn’t submerged.

3. After 2 hours, take out items and, using old towels, sponges or the like, gently press out excess liquid.

4. Allow to air dry. Once fully dried, treat with the leather dressing of your choice: I use a paste of olive oil & beeswax (4 to 1) with a few drops of clove oil to keep off the mould.

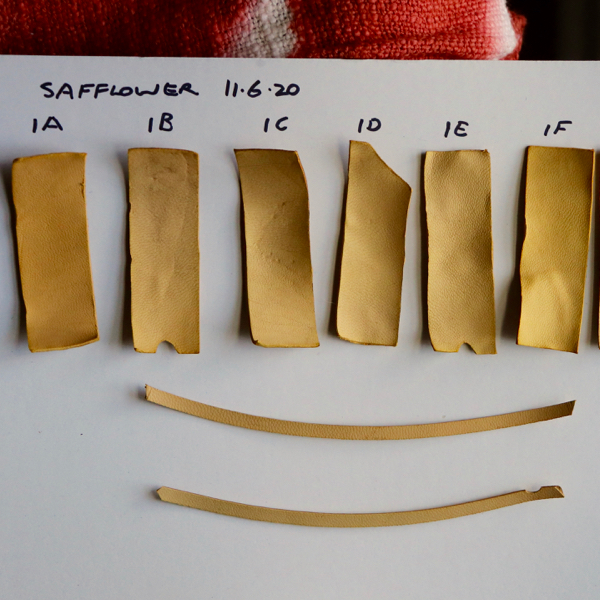

Some experiments on sheepskin with different method combos – alum then cold dye; cold no alum; alum then dye starting cold then heated; alum then hot dye; hot no alum; reused hot bath after cooling and dyed overnight. Cold baths gave buttery yellows. If the dye gets heated at any stage, lemon yellows result. Without alum, only dull buff tones.

Yellow dyes don’t like light

Light is the bane of all natural yellow dyes. I put some test strips outside for a couple of days. Though I expected them to fade, the ends exposed to the sun darkened – but went a bit brown unfortunately.

What about weld…

I hear you say? The best beloved yellow dye of medieval textiles? Weld didn’t work for me at all – I tried fermenting the plant; dyeing hot or cold; with or without mordanting; all lengths of time. The dye solutions looked intense but it just wasn’t taken up by my leather – thoroughly discouraging. Yellow dyes from the tannin family are another historical possibility: pomegranate shell is involved in making traditional Moroccan yellow leather. I suspect there’s more to be found out here as I could only get buff to cinnamon tones, at least from the powder I bought.

Dye agents, and inspiration from maiwa.com

Other reference: Dominique Cardon. Natural Dyes: Sources, Tradition, Technology and Science. Archetype: London 2007. ISBN 978-1-904982-00-5

*Fun fact: Safflower is traditionally used to dye proper government ‘red tape’ (oh yes, Minister – thats a real thing, look it up!)